Universal design: How to grow audiences by centering the outsider

Originally published on November 15, 2022.

What does an architect in a wheelchair have to do with growing arts audiences? Hear me out:

Ronald Mace was disabled by polio at the age of nine. Influenced by his experience navigating life in a wheelchair and constantly feeling different as a disabled individual, Mace earned a degree in architecture. But he quickly became passionate about inclusion by design.

Humanity’s vast diversity is best celebrated, he realized, by inclusion that does not highlight differences, but instead equalizes by removing all barriers.

Mace coined the term universal design, which he defined as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for specialized design.”

So what does this have to do with orchestras, ballet companies, theaters, opera companies, and museums?

The key here is this: There’s no such thing as average.

Beyond Accessibility: A Framework for Innovation

While the concept of universal design began as an approach meant to help reduce barriers—both physical and attitudinal—between people with and without disabilities, it has become adopted by many sectors.

In education, for example, traditional methods typically focus on the average user, requiring students with differences to seek accommodation. Using the universal design approach in education, writes leading expert Sheryl Burgstahler, “helps to streamline the accommodations process by eliminating deficits in products and environments that make them inaccessible to some people.”

The big pivot? Highlighting not the individual’s differences but the environment’s deficits.

Forward-thinking leaders are applying universal design principles across entire organizations, recognizing that inclusive design fosters innovation that benefits everyone.

"Universal design is the practice of designing all organizational systems...to focus on the experience of those who are most marginalized,” writes organizational development expert Beth Zemsky. “By centering the experience of those who are most marginalized, we most often find that systems are created that function better for all of us.”

Take curb cuts, for example. Originally designed for wheelchair users, they’re an innovation that everyone benefits from: parents with strollers, delivery workers with dollies, travelers with rolling luggage, cyclists.

Or closed captions. Created for deaf and hard-of-hearing viewers, they’re now used by people in noisy gyms, quiet libraries, by language learners, and anyone watching videos on mute.

Or automatic doors. Designed for people with mobility issues, but helpful for anyone carrying packages, pushing a cart, or using crutches temporarily.

The Inclusion Problem in the Arts

So what does the concept of universal design have to do with the arts? When we look at the data, the numbers tell a story of exclusion:

In 2019, according to Colleen Dilenschneider’s research, 89.1% of orchestra patrons identified as White—despite the fact that Indigenous, Black, and People of Color represent 40% of the U.S. population.

“The audience composition of US cultural organizations,” Dilenschneider wrote, “overrepresents the US population of White non-Hispanic individuals.”

Could this be solved by universal design?

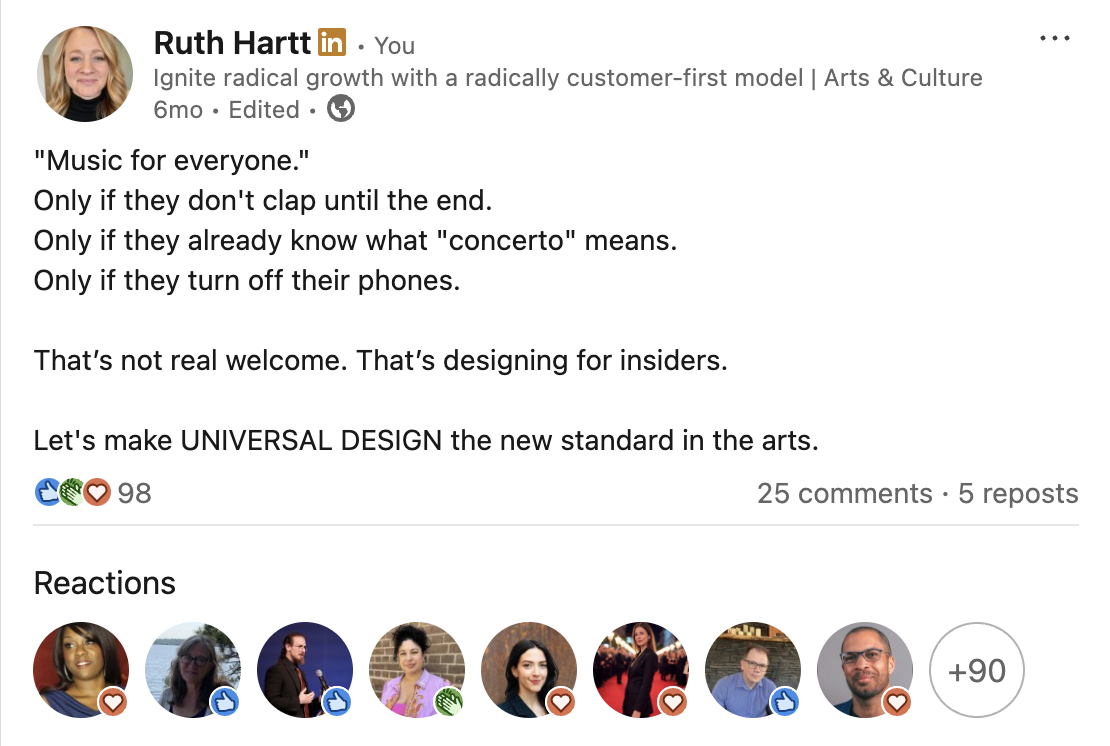

In the arts sector, we find a focus on the “average user” (the Loyals) and an insistence on long-held traditions that, in effect, force other potential patrons to avoid the space altogether.

These traditions result in experiences and messaging that assume everyone shares the same cultural knowledge and the same motivations. When we design around these assumptions, we create invisible barriers that keep people out. If inclusion in the arts is about all people benefiting from the powerful outcomes that the arts can provide, traditional assumptions aren’t helping us meet that goal.

The Barrier of Relevance

This is where universal design and radically customer-first thinking converge. When we center the experience of nonconsumers, we discover that inclusion doesn’t start with demographics or ticket price—it starts with relevance.

In the end, relevance is a form of access. And breaking through that barrier can be just as transformative as breaking through a financial one.

Asking “How do we make our traditional offering accessible to more age groups and ethnicities?” usually results in sustaining innovations (like discounted tickets) that don’t sufficiently move the needle for access, because they don’t address the underlying cause.

Product-agnostic questions, like “What motivations drive the behavior of today’s consumer, and what barriers prevent them from finding what they need in the arts?” help us center the experience of the nonconsumer or the Outsider. They force us to step outside our existing assumptions and look at human needs first.

When you start with human needs instead of your product, you discover opportunities to serve people your traditional approach misses. This kind of strategy opens up access to more diverse audiences, because it taps into their perceptions of value and increases the relevance of the arts in their eyes.

In the end, relevance is a form of access. And breaking through that barrier can be just as transformative as breaking through a financial one.

The Seven Principles

But what does it look like to design in ways that allow everyone to engage equally? The seven principles of universal design offer a concrete roadmap for arts organizations ready to make this shift.

Consider Principle 3: Simple and Intuitive Use. This means eliminating unnecessary complexity and accommodating diverse knowledge levels—exactly what happens when organizations provide accessible program notes or clear behavioral expectations rather than assuming cultural fluency.

Or Principle 2: Flexibility in Use, which calls for providing choice in methods of engagement. An arts organization applying this principle might offer multiple ways to experience the same content: traditional silent concerts, interactive discussions, or social media engagement during performances.

These aren't accommodations for 'different' people—they're design improvements that make experiences better for everyone.

Universal Design in Practice

What if we applied the universal design framework across the arts sector? What if we took a deep interest in the marginalized—the Outsiders, the uninitiated, the nonconsumers—and removed any barrier that might make it difficult for them to engage?

This is exactly what Priya Parker advocates in her book The Art of Gathering, though she approaches it through the lens of hosting rather than design. Her framework for creating inclusive gatherings mirrors universal design's core principle: when we design for those who face the greatest barriers, everyone benefits.

Parker advocates for breaking down exclusionary barriers by intentionally rethinking tradition and longheld rules of etiquette.

“The etiquette approach…” she writes, “shows minimal interest in how different cultures or regions do things. It upholds a gold standard of behavior as the only acceptable one for people who wish to be seen as refined. It is not interested in variety or diversity.”

When we center the experience of our Loyals, we celebrate the traditions of the past. When we center the experience of those traditionally marginalized by our sector, we celebrate the diversity of the present.

Here’s how I read this: When we center the experience of our Loyals, we celebrate the traditions of the past. When we center the experience of those traditionally marginalized by our sector, we celebrate the diversity of the present.

Sound daunting?

Parker actually keeps it very simple. A good host, she says,

protects their guests,

connects their guests, and

equalizes their guests.

When we approach our work through the lens of universal design, we protect our guests by making implicit expectations explicit. We connect our guests by creating opportunities for meaningful interaction. And we equalize our guests by removing the barriers to belonging and revealing the real-world relevance of the arts.

Ready to center the outsiders?

The answer lies in understanding what your database can't tell you about your audiences.